January 20/21, 2024: Santa Cruz Symphony was back in force again this weekend for concerts that included a world premiere and two works for large orchestra, the Adagio of Mahler’s unfinished Symphony No. 10 and Ravel’s second Daphnis et Chloé suite.

The program began, however, with tributes to two recently deceased members of the orchestra family. First, orchestra board president Linda Burroughs introduced a video tribute in memory of Rowland (“Reb”) Rebele, who died in November. Reb, who has been described as “a philanthropic giant,” had long been an unwavering supporter of the orchestra. [READ MORE ABOUT ROWLAND REBELE HERE.]

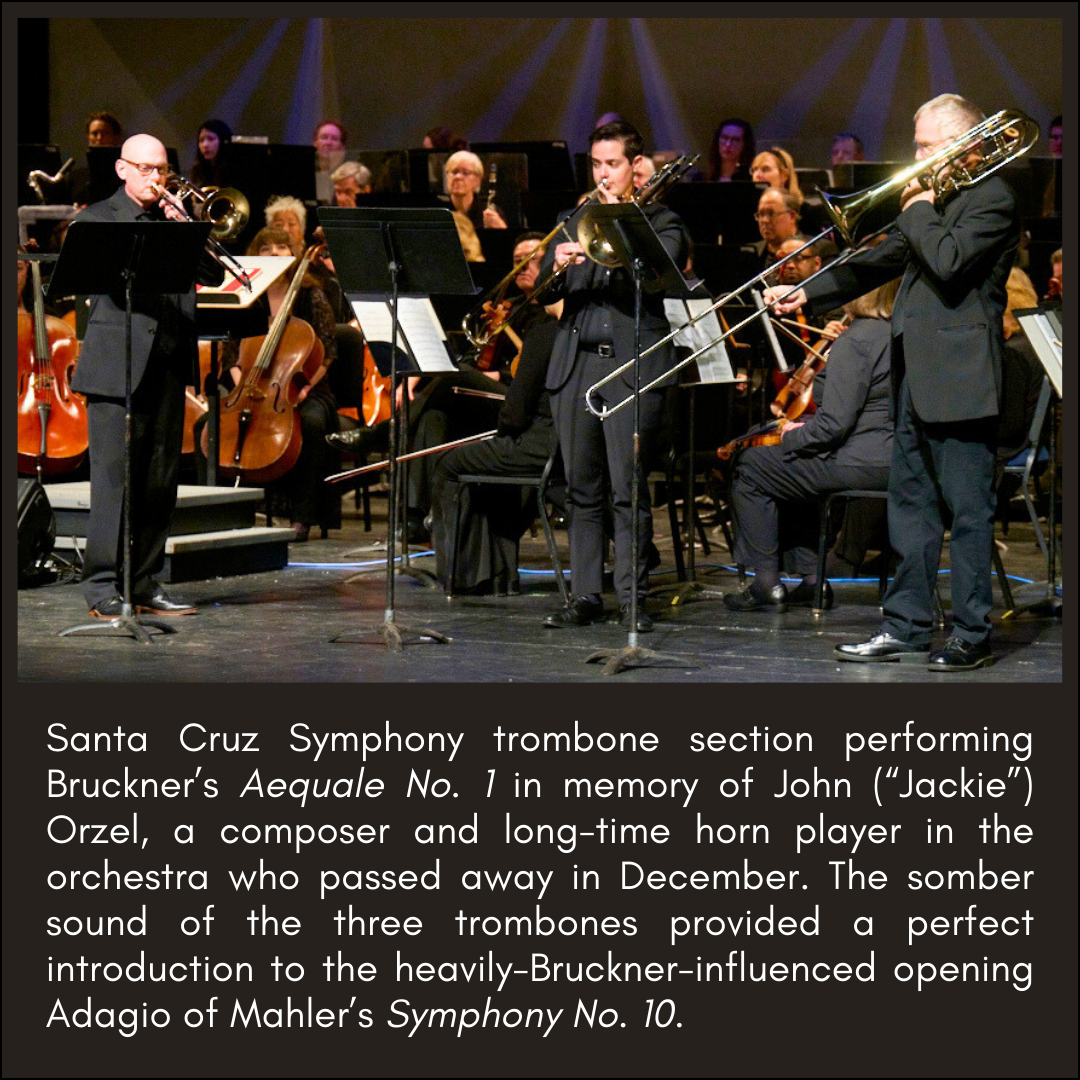

BRUCKNER’S AEQUALE NO. 1

After the video, music began with a tribute in memory of John (“Jackie”) Orzel, a composer and long-time horn player in the orchestra who passed away in December. Jackie’s favorite composer was Anton Bruckner and Jackie’s daughters proposed playing Bruckner to honor their father’s memory. The orchestra’s trombone section therefore played Bruckner’s Aequale No. 1. The somber sound of the three trombones provided a perfect introduction to the heavily-Bruckner-influenced opening Adagio of Mahler’s Symphony No. 10.

MAHLER’S ADAGIO FROM SYMPHONY NO. 10

Before the pandemic interrupted, Maestro Daniel Stewart and the Santa Cruz Symphony were nearing the midpoint of a spectacular Mahler cycle. By the time performing arts shut down in 2020, the orchestra was at four symphonies down and five-plus to go. They had played half the symphonies that were performed in Mahler’s lifetime. I’m delighted to be now able to report that, with Saturday’s concert in the Civic Auditorium, the Mahler cycle in Santa Cruz County has resumed.

What do you write after you’ve written your farewell to life? Based on the cases of Bruckner and Mahler, the answer would seem to be whatever it is, you will die while writing it! Bruckner’s “Farewell to Life” was the Adagio third movement of his 9th symphony. He died while working on the finale of the symphony. Mahler’s celebrated and much-discussed “Farewell to Life” is the last movement of his 9th symphony. He immediately started a 10th symphony, but he too died while working on his last symphony. In both cases, others have offered multiple completions of the unfinished symphonies. This presents an obvious problem for conductors of cycles of the Mahler symphonies: what does one do about the unfinished 10th? Daniel Stewart, like many other conductors, has opted to just do the completed opening Adagio movement. The audience was not short-changed though, because this movement lasted 25 minutes, the same length as all of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 1.

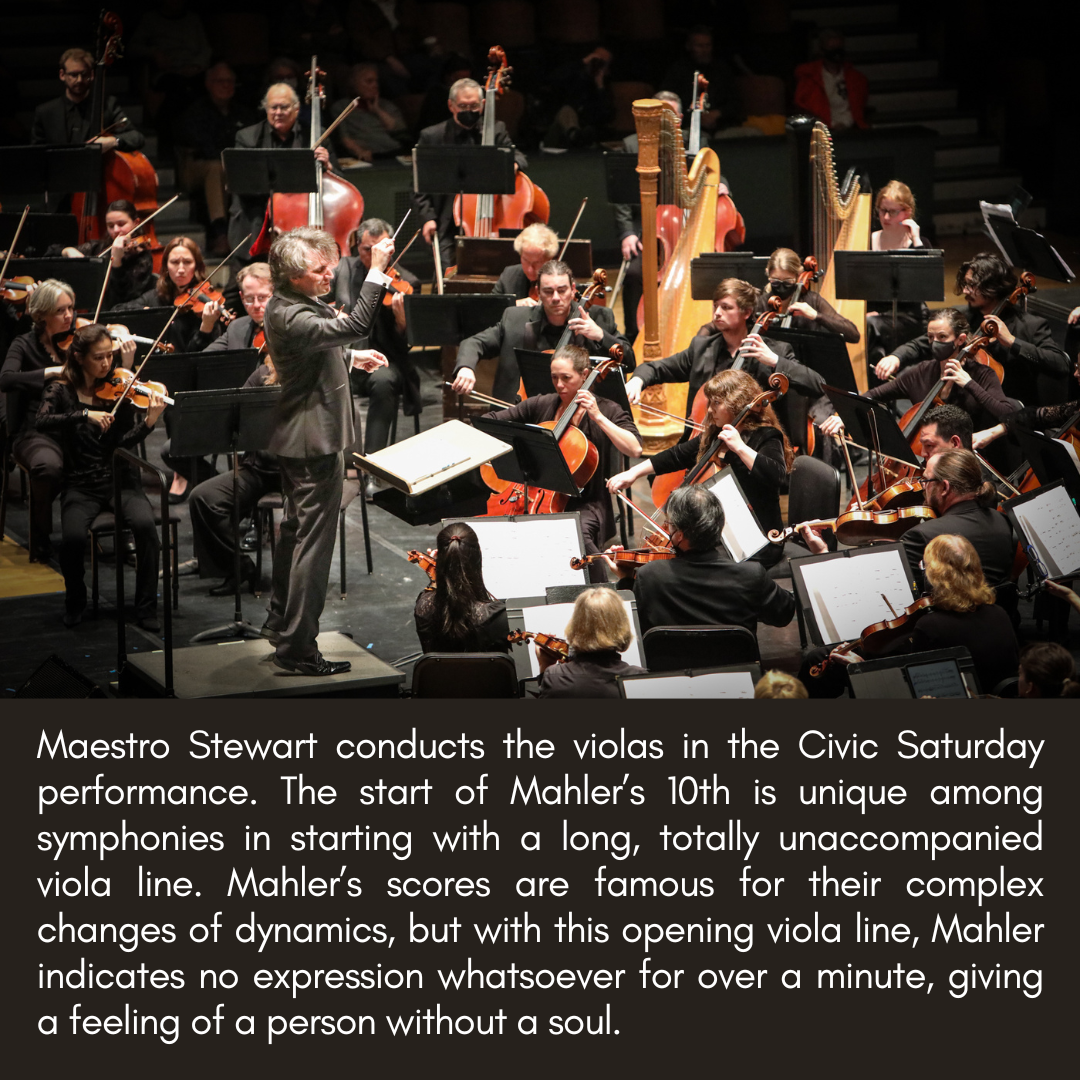

The start of a work is the important time when the fresh mind of the listener is exposed to key ideas. The start of Mahler’s 10th is unique among symphonies in starting with a long, totally unaccompanied viola line. After the applause for the Bruckner Aeauale had died down and the trombones were back in their seats, the viola section began their pianissimo line. Mahler’s scores are famous for their detailed and complex changes of dynamics but, strikingly, with this opening viola line, Mahler indicates no expression whatsoever for over a minute. The viola is the most human of the strings. Unlike the other members of the string family, the notes do not go out of the range of the human voice. The lack of expression in the stark opening viola passage and the two similar unaccompanied viola passages later in the movement give a feeling of a person without a soul. Recognizing the importance of the violas’ contribution, Maestro Stewart asked the viola section to stand for a solo bow at the end of the Mahler. The audience responded with enthusiastic applause.

The bare, tonally ambiguous viola line cries out for warm harmony to follow and Mahler does not disappoint. The violas are followed by lush string harmonies supported by the three trombones. Playing such rich, warm string writing is something Daniel Stewart and the orchestra excel at. With its harmonic vocabulary and with the wide leaps in the string parts the string writing shows strong influences of Bruckner’s last symphonies, especially his unfinished 9th. This is unsurprising since, Mahler who had been part of Bruckner’s inner circle as a student and who was later to pay for the reprinting of Bruckner’s symphonies, visited Bruckner multiple times as the older composer was struggling to complete his 9th symphony before dying. Now it was Mahler who was dying and struggling to finish his last symphony.

The second violins deserve special praise for their performance in the Mahler. In orchestras, it is invariably the first violins who must play the difficult violin parts up in high positions. The second violins stay in a less demanding, more comfortable lower register. Not so in Mahler’s 10th. The wide-ranging and passionately leaping string lines frequently take the second violins high above the firsts up to the very extremes of the violin range. In their perfect execution of these extremely high passages, the second violins of the Santa Cruz Symphony proved that they were just as capable as first violinists.

An amazing trumpet solo by newly promoted principal trumpeter Alan Matteri must be singled out. About 18 minutes into the movement there is an awe-inspiring, very Brucknerian moment when the full brass suddenly enters, triple fortissimo. This is followed by two loud sustained dissonant chords. After each of these, the first trumpet holds a totally exposed, high concert A for a quarter of a minute, a duration that seems like forever.

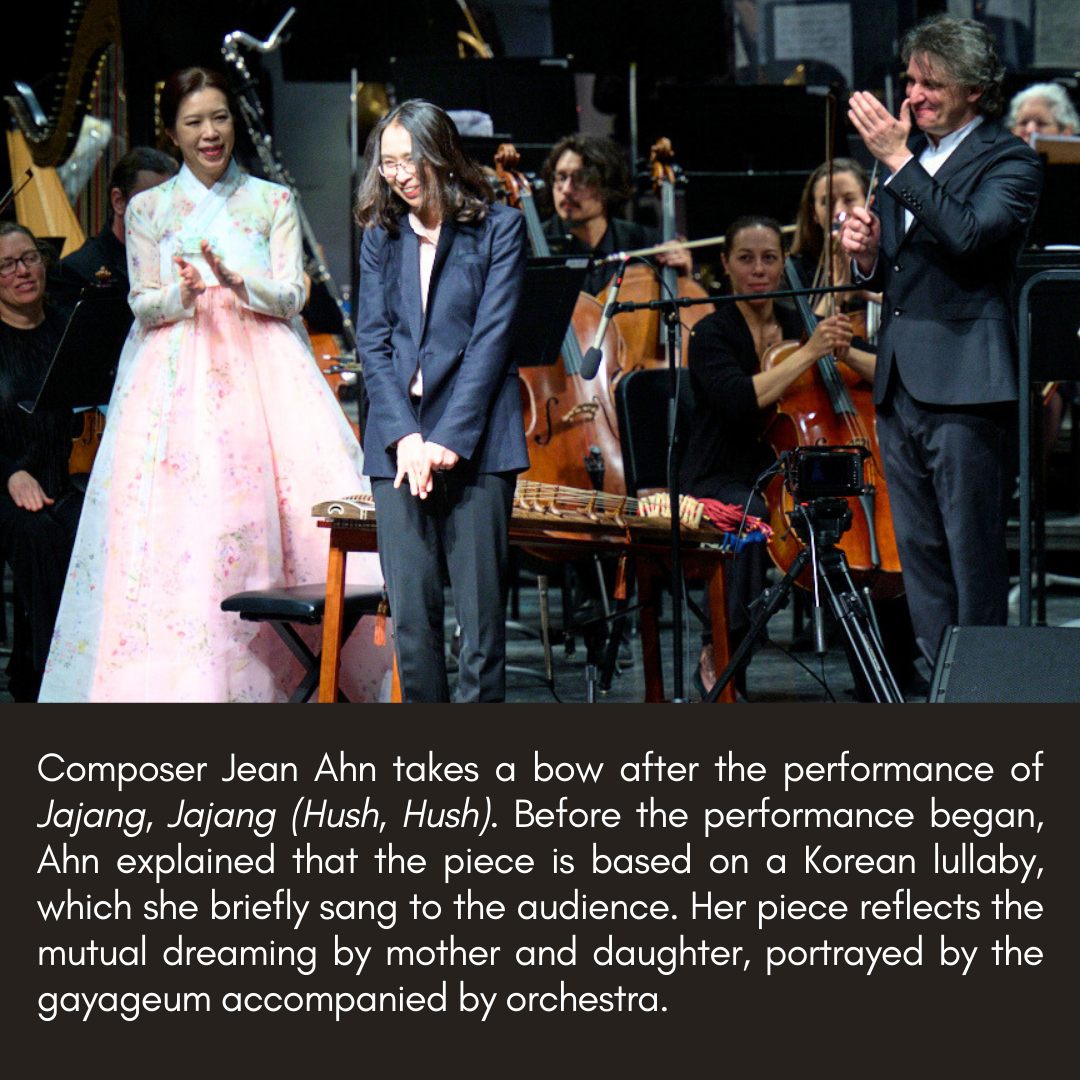

JEAN AHN’S JAJANG, JAJANG

After the intermission the audience was treated to the première of Jean Ahn’s Jajang, Jajang for Korean gayageum and orchestra. The soloist was Hwayoung Shon. The gayageum is a long horizontal plucked instrument.

Since it is quiet compared with a full orchestra, the gayageum was amplified. Cameras were set up to show the gayageum on the large projection screen so that the audience could appreciate the speed and accuracy with which Hwayoung Shon’s fingers moved. She wore a colorful traditional Korean dress that made a visually appealing contrast to the all-black of the orchestra.

Jajang, Jajang is based on a well-known Korean lullaby. The title translates loosely as “hush, hush.” Composer Jean Ahn briefly sang the lullaby to the audience before the performance of her piece and explained that she used to sing it to her baby daughter to encourage her to fall asleep so that Ahn herself could get some sleep. (Mothers in the audience clearly related to this!) Ahn said that she realized that her baby daughter was dreaming and that she herself in her half-awake state was also dreaming. She explained that her piece, Jajang, Jajang is not a lullaby but instead reflects the mutual dreaming of mother and daughter. The dreams are portrayed by the gayageum accompanied by a diverse range of orchestral sounds and textures. The piece was warmly received by the audience.

RAVEL’S DAPHNIS ET CHLOE SUITE NO. 2

To conclude the concert the orchestra returned to the start of the second decade of the 20th century and played a virtuoso showpiece: Ravel’s second Daphnis et Chloé suite. It is interesting to note that Mahler’s 10th Symphony and Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé were both being written at the same time, at the end of the golden age of Romantic music when composers such as Elgar, Rachmaninoff, and Sibelius were at the height of their powers.

For Daphnis et Chloé, Ravel uses a large orchestra. This includes three clarinets, a bass clarinet, an E-flat clarinet, four flutes with three of the players doubling on piccolos or alto flute, and a large percussion section of seven players. Ravel also provides for an optional, off-stage, wordless chorus, but the singers were omitted in last weekend’s performance, as they are in most performances. Ravel’s score is very rich and opulent with a lot going on and a huge number of notes. Impressively, Maestro Stewart conducted this very complicated work from memory!

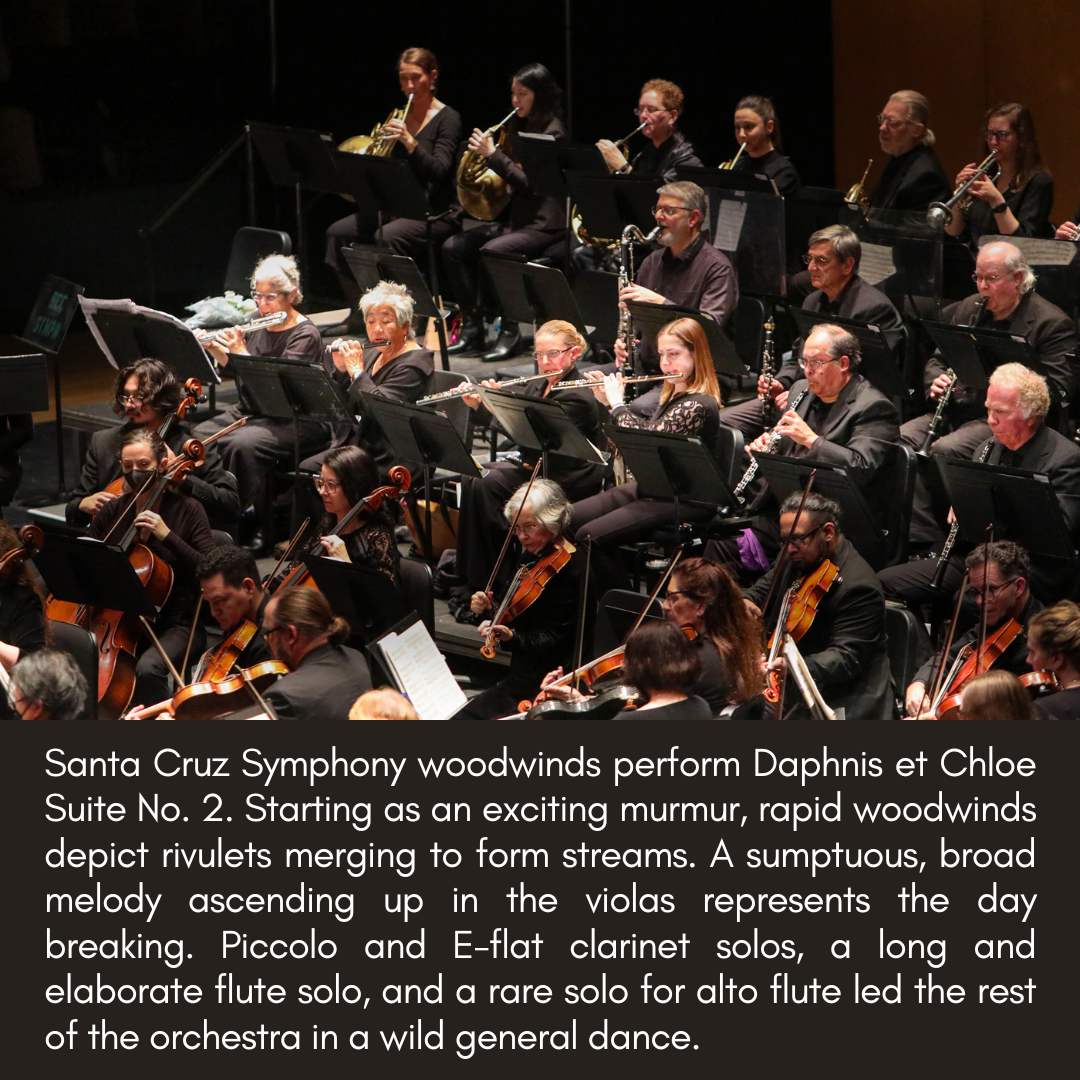

The details of what each part of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 10 or Jean Ahn’s Jajang, Jajang means is left open to speculation, but with Daphnis et Chloé we are in no doubt because it was a ballet. The suite opens with a celebrated depiction of daybreak. It is in the style of a so-called “French toccata” where rapid notes in the treble define slow-moving harmony and the melody is mostly in the lower parts. Starting as an exciting murmur, rapid woodwinds, and figures depict rivulets merging to form streams. A sumptuous, broad melody ascending in the violas represents the day breaking. Piccolo and E-flat clarinet solos (Leslie Chin and Michael Corner respectively) correspond to characters appearing on stage. As the broad melody rises into the violins, the lovers embrace. (The violas have a larger share of prominent parts in this concert than usual, but when it comes to accompanying lovers embracing, composers do seem to think it is a job for violins, not violas!)

The central part of the suite is Daphnis and Chloé doing a pantomime of the story of Pan and Syrinx. Pan is famous for his pipes, of course, so we had a long and elaborate flute solo skillfully played by acting principal flute Sarah Benton, who received loud applause at the end of the concert. Daphnis et Chloé also includes a rare solo for the alto flute (played by Maria Concus.)

The third and final part of the suite is a wild general dance and so another Santa Cruz Symphony Orchestra concert came to an exciting close.

— Professor Martin Gaskell