Reviewer Josef Sekon

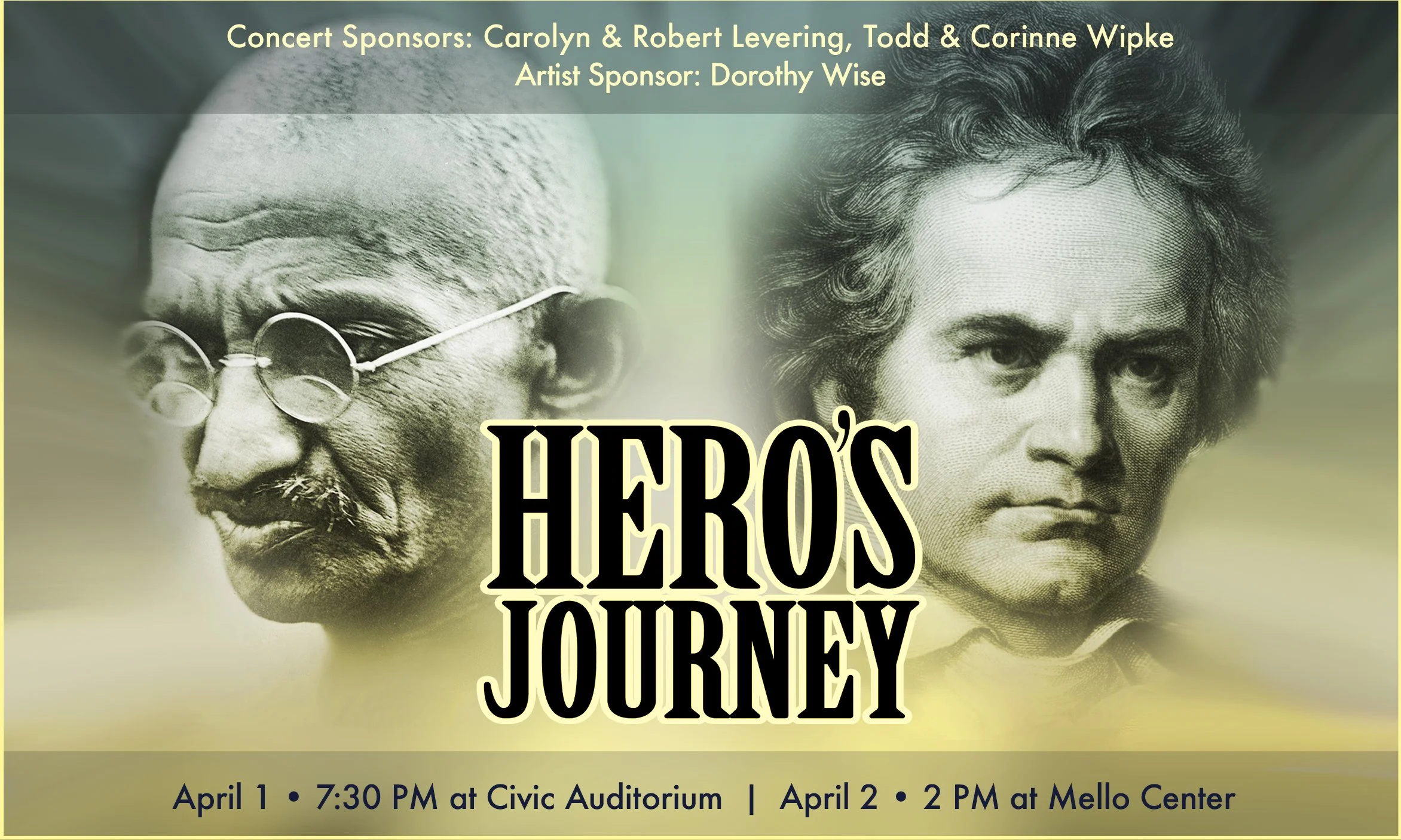

The concert began with Seven Decisions of Gandhi (2020) by William Harvey (1982) featuring the composer on violin. This performance was the West Coast World Premiere of this most interesting work. Harvey read and was influenced by Ramachandra’s two books on Gandhi’s life and was inspired to compose this work.

On June 28, 2020, Harvey wrote: “After a month of very hard work, I am thrilled to present to the world the concerto I just composed for violin and orchestra. It takes as its premise that we are defined by our decisions.” The “month of very hard work” was worth every minute, a solid composition and performance. They’re a nicely diverse selection, with well-balanced sound between orchestra and soloist throughout, performing crisp, lustrous sound collaboration that, like the Chameleon, permeated and absorbed the seven parts:

I. S.S. Clyde to London

II. Selling the Violin

III. Phoenix

IV. Hartel

V. Khadi

VI. Chauri

VII. Salt March.

The pacing was perfect. Stewart and the orchestra richly detailed Harvey’s musical language with compassion. As an added surprise feature, Jim Santi Owen provided an artistic role on tabla. The second movement offered up a taste of Middle Eastern flavor implementing large Almglocken, metal percussion, and rhythmic pizzicato. Part III offered a well-orchestrated minor chord and set a tranquil mood as the table wove its way through the orchestral texture.

Part IV demonstrated Harvey’s skill as a composer. Upbeat orchestral moments, with virtuoso solo violin, effective brass writing provided a creative sound backdrop for the violin/harp. This section offered subdued, drifting moments of attractive orchestral color. VI and VII provided an impressive show of rhythm, creativity, virtuosity, and orchestral understanding with an ending that faded into the atmosphere.

Soloists Harvey and Owen performed an encore duet of an Afghan song, creative and delightfully performed in every possible way.

Ludwig van Beethoven’s 1803 Symphony No. 3 in Eb, Op. 55 (Eroica) marked the turning point in his artistic output. With the Eroica, Beethoven raised the symphony to an unprecedented level of expression and grandness of musical conception. Compositional elements such as its daring length, range, and emotional commitment marked something of a new beginning in the development of symphonic structure and prompted endless discussions among critics about what it all meant. Following the symphony’s first performances, several critics regarded the work as “a dangerously immoral composition and a daring wild fantasia of inordinate length and extreme difficulty of execution.” Today, it is considered the finest symphony of the historical period! The second movement played an important role during the procession carrying the Queen’s coffin from Buckingham Palace to Westminster Hall where she lay in state.

Stewart approached the work with a great affection, offering up music of urgency and emotion, to be sure, but also of resplendent love, stately nuances, and sublime musical caresses by the orchestra. It was the kind of performance that was hard for one not to find appealing in all respects. The opening chordal strokes that introduced us to Beethoven's vision were razor-sharp, well-balanced, and precise. With many conductors, at times the notes sound sharp and concise; with Stewart, they sounded strong, full, but mellower, more resigned. It's as though the conductor wanted us to know at the outset that this is going to be a more benign, more humane, artistic interpretation than you've probably heard before.

Of special impressive note was the historic move by the cellos in measure 7, when C# appeared and resolved to D, marked by dramatic emphasis by the orchestra. The question-answer fughetta section began in measure 236 and carried through its ingenious dissonant culmination of extraordinary intensity in measure 280. Beethoven’s use of the hemiola that entered in measure 449 of the first movement by the flutes, oboes, and clarinet was extensive and carried melodically by the use of the amphibrach rhythmic organization (weak – strong – weak).

The second-movement funeral march (Marcia funebre) is designated Adagio assai (very slowly) and alludes to somber introspection. Rather than bring out only the stateliness of the music, Stewart chose to bring out the inner beauty of this movement. His interpretation and time of the well-known Marcia funebre. Adagio assai fit perfectly into many performances by well-known conductors. Chronologically: Paavo Jarvi 13:03, Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen; Sir Simon Rattle 15:10, the Vienna; Bernard Haitink, 15:15, Concertgebouw Orchestra; Gustavo Dudamel 16:13, the Simon Bolivar Orchestra; and Ricardo Muti and the Philadelphia Orchestra 18:11. Sunday’s performance at the Mello, Maestro Danny Stewart chose the time of 16:27.

Of course each performance will be uniquely altered in time. But Stewart’s choice of tempo allowed him to paint with a more varied orchestral palette—when desired, developing a darker, more forlorn atmosphere. Scrupulous attention to dynamics and articulation appeared here as well, as did the fastidious care taken in clarifying Beethoven’s contrapuntal textures.

The oboe part in measures 8 through 16 were performed with palpable emotional commitment. Winds, brass, timpani, and harp were simply fabulous throughout! The fragmentation of the theme at the end was masterfully handled, the last bars deeply touching. The lean and graceful playing heard in the first movement reappeared in the Scherzo, but the brazen coloring of the horns in the trio section was exceptionally thrilling. The final movement responded even more favorably to Stewart’s interpretative stance, each dazzling variation dispatched with a technical finesse and engaging brio that celebrated Beethoven’s brilliance. It was fascinating to hear such a different timbre and weight to the sound. Then we got the driving Finale with a reassuringly triumphant conclusion.

The upbeat tempo of the Coda was delightful and allowed for great clarity (the horns clearly articulated their fabulous lines) and a grandly noble conclusion. In the Finale, Stewart was willing to embrace the unbridled rowdiness of this music, bringing a sense of wild jubilation that left the listener elated. Surely this is what Beethoven intended. Very well realized and accomplished Maestro and Santa Cruz Symphony!

JOSEF SEKON, D.M.A.